VACEP's EBM Series: Low-Risk Criteria to Evaluate Fever in Infants

VACEP Evidence-Based Medicine for General Emergency Physicians Series

Authors: Joshua Easter, MD, MSc | UVA Faculty; Justin Yaworksy, MD | UVA Resident

Reviewers: Matt Jordan, MD | Naval Medical Center Portsmouth Faculty; Jessica Arnott, MD | NMCP Resident

Case

A 26-day-old female presents to your emergency department (ED) with a fever to 100.8°F. She is well appearing, asymptomatic, and has an unremarkable medical history. What are your next steps in the evaluation of this febrile infant?

The appropriate diagnostic evaluation for febrile infants remains unclear. Numerous clinical prediction models and guidelines have attempted to balance a highly sensitive approach that does not miss bacterial infections with a reasonably specific approach that minimizes the potential harms associated with testing, treatments, and hospitalizations (1-7).

New vaccinations, evolving frequency and bacteriology of infections, increased prenatal screening, and novel diagnostic tests (e.g. procalcitonin, rapid viral tests) have altered the landscape for the evaluation of pediatric fever. As discussed in a prior VACEP review, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recently published a clinical practice guideline on the evaluation and management of well-appearing febrile infants 8 to 60 days in age that attempts to address this shifting landscape (8,9).

Notably, these guidelines rely heavily on expert opinion and have not been validated. Validation is a crucial step before implementation of the guidelines..

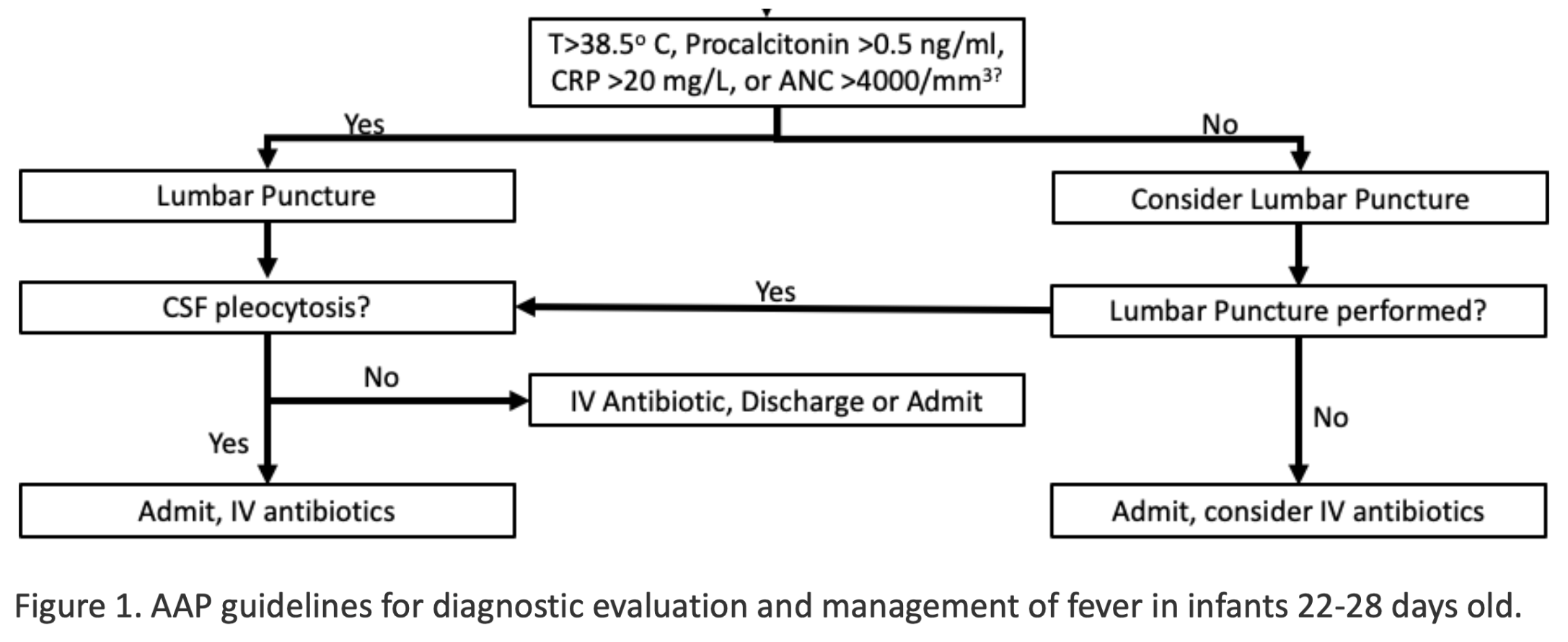

Figure 1. AAP guidelines for diagnostic evaluation and management of fever in infants 22-28 days old.

In June of 2022, Burnstein et al. published a large validation of an important component of the AAP guidelines (10). The AAP identified procalcitonin as the most accurate inflammatory marker for risk stratification in fever, but acknowledged it is not readily available.

As an alternative, the guidelines suggest utilizing temperature, C-reactive protein (CRP), and the absolute neutrophil count (ANC) to guide management. Specifically, for infants 22-60 days old, the AAP guidelines indicate the presence of a temperature <38.5 °C, CRP < 20.0 mg/L and ANC < 5200/mm3 place children at low risk for invasive bacterial infection (IBI), including bacteremia and bacterial meningitis, and, therefore, lumbar puncture and admission may not be required (Figures 1 and 2)(8).

Figure 2. AAP guidelines for the diagnostic evaluation and management of fever in infants 29 to 60 days old.

To validate these AAP recommendations, Burnstein et al. performed a secondary analysis of quality improvement data collected prospectively by Montreal Children’s Hospital from January 2018 to October 2021. All infants had blood and urine cultures obtained, while cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) was collected at the discretion of the treating physician. The primary outcome was invasive bacterial infection (bacteremia or bacterial meningitis), and the secondary outcome was serious bacterial infection (SBI) - bacteremia, bacterial meningitis, or urinary tract infection. The study included all previously healthy, well appearing, term-born infants from 8-60 days that met the AAP inclusion and exclusion criteria, including lack of a clear source for the infant’s fever (10).

Of the prior study’s population, 92% (957/1041) of infants met inclusion criteria and had complete data, including telephone follow-up at 14-28 days if they did not undergo lumbar puncture. 3% (27/957) of infants had invasive bacterial infections, and 17% (164/957) had serious bacterial infections, including urinary tract infections. The AAP criteria classified 45% of infants as low risk, and there were no cases of bacteremia or bacterial meningitis in this low risk group. Thus, the overall sensitivity for the AAP criteria for without using procalcitonin meningitis and bacteremia was 100% (95% CI: 87-100%).

When expanded to include urinary tract infections, the sensitivity for serious bacterial infections declined to 84% (95% CI: 78-89%). Notably, two thirds of these missed urinary tract infections had an abnormal urinalysis. When the ANC threshold was reduced to >4000, which is an alternative cutoff recommended by the AAP when procalcitonin is also evaluated, the sensitivity of the low risk criteria remained 100% for bacteremia and bacterial meningitis (10).

About the EBM Review Series

This is a relaunch of the literature review series started by Josh Easter at UVA, a VACEP board member working to connect the academic community in Virginia. We invite each residency in Virginia (and D.C.) to create a faculty/resident team to submit and review articles. Email Executive Director Sarah Marshall to take the next step.

Goals

Provide a brief monthly synopsis of a high yield article germane to the practice of emergency medicine for distribution to all VACEP members

Provide an opportunity for a peer reviewed publication and invited presentation for faculty and trainees

Foster an academic community focused on evidenced based medicine for emergency medicine residency programs in the region

The VACEP EBM series would like to thank Drs. Matt Jordan and Jessia Arrott from the Department of Emergency Medicine, Naval Medical Center Portsmouth for their expert peer review of this article.

While this study suggests the new AAP guidelines have good sensitivity for identifying low risk infants 22-60 days of age, several important limitations exist, which should caution the clinician from utilizing this criteria alone to rule out bacterial infections. This was a single-center study at an academic Children’s Hospital, and the results may not extrapolate universally to other EDs, especially community hospitals and other patient populations. The study relied on a convenience sample of patients with data on all inflammatory markers, which may have led to selection bias.

For example, patients deemed low risk by clinical gestalt may not have undergone extensive laboratory testing and, therefore, may have been excluded from the prior study. Alternatively, it is possible clinicians did not obtain inflammatory markers for patients deemed higher risk based on clinical gestalt, because the clinician planned to admit the patient regardless of the markers. Either of these selection biases could alter the results. Another limitation is the inclusion of 178 infants 8-21 days old.

The AAP does not recommend utilizing inflammatory markers to alter the diagnostic evaluation of these infants, and, therefore, it is unclear why these patients were included in a study evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of inflammatory markers. Notably, the authors did separately analyze children 22-60 days, and the sensitivity of the AAP criteria remained 100%, albeit with a reduced lower bound of the 95% confidence interval of 81%.

The lower bound of the 95% confidence interval is a major limitation for this study, as it suggests the low risk criteria could miss as many as 19% of cases of bacteremia or bacterial meningitis. For comparison, the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval for the sensitivity of the New Orleans Criteria, a well known prediction model for traumatic brain injury in adults, is 97% (11). We suspect this frequency of missed diagnoses for the high morbidity conditions associated with infant fever would be unacceptable to most emergency physicians. Unfortunately, this is an issue with most studies of infant fever due to the low prevalence of invasive bacterial infections in this population. In order to further validate these guidelines, an appropriately powered study with a larger patient population could establish tighter confidence intervals around the diagnostic accuracy of the tests.

The guidelines also suggest potential hospital admission and observation for infants aged 22-60 days not undergoing a full sepsis work-up. While this may reduce testing, it could lead to increased frequency of hospitalization and, thereby, resource utilization. Finally, the guidelines rely on the clinician determining if the patient is well appearing, which can be challenging with febrile infants.

The primary strength of this study is that it represents the first large external validation of the AAP guidelines. Validation is a crucial step before widespread adoption of guidelines. In addition, by excluding procalcitonin, this study improved the generalizability of the overall AAP guidelines. However, the lower bound of the confidence interval for the diagnostic sensitivity of the guideline identified in this study suggests that the low-risk criteria could potentially miss a significant number of clinically important infections. Without further validation, we recommend clinicians utilize caution in relying exclusively on inflammatory markers to rule out bacterial infections in infants 22-60 days of age.

Conclusion

Your patient is well appearing and there is no clear source for her fever. Therefore, it would be reasonable to consider utilizing the AAP guidelines. If her ANC and CRP are normal, she would qualify as low risk by the AAP guidelines and not necessarily require lumbar puncture. Unfortunately, the lower bound of the 95% confidence interval for the AAP’s new low risk criteria for infants 22-28 days in this study was only 48%, suggesting the low risk criteria could miss as many as half of cases of bacteremia or meningitis. As a result, without further validation it would be prudent to utilize alternate criteria to manage this febrile infant, such as the Boston or Rochester fever criteria.

REFERENCES

Scarfone R, Gala P, Sartori L, et al. Febrile infant clinical pathway - emergency department. Febrile Infant Clinical Pathway - Emergency Department. https://www.chop.edu/clinical-pathway/febrile-infant-emergent-evaluation-clinical-pathway. Published August 12, 2010.

Murray AL, Alpern E, Lavelle J, Mollen C. Clinical Pathway Effectiveness: Febrile Young Infant Clinical Pathway in a Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2017 Sep;33(9):e33-e37. doi: 10.1097/PEC.0000000000000960. PMID: 28072664.

Bachur RG, Harper MB. Predictive model for serious bacterial infections among infants younger than 3 months of age. Pediatrics. 2001 Aug;108(2):311-6. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.311. PMID: 11483793.

Dagan R, Powell KR, Hall CB, et al. Identification of infants unlikely to have serious bacterial infection although hospitalized for suspected sepsis. J Pediatr. 1985;107:855–860.

Jaskiewicz JA, McCarthy CA, Richardson AC, White KC, Fisher DJ, Dagan R, Powell KR. Febrile infants at low risk for serious bacterial infection--an appraisal of the Rochester criteria and implications for management. Febrile Infant Collaborative Study Group. Pediatrics. 1994 Sep;94(3):390-6. PMID: 8065869.

Mintegi S, Bressan S, Gomez B, Da Dalt L, Blázquez D, Olaciregui I, de la Torre M, Palacios M, Berlese P, Benito J. Accuracy of a sequential approach to identify young febrile infants at low risk for invasive bacterial infection. Emerg Med J. 2014 Oct;31(e1):e19-24. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2013-202449. Epub 2013 Jul 14. PMID: 23851127.

Kuppermann N, Dayan PS, Levine DA, et al. Febrile Infant Working Group of the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN). A Clinical Prediction Rule to Identify Febrile Infants 60 Days and Younger at Low Risk for Serious Bacterial Infections. JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Apr 1;173(4):342-351. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5501. PMID: 30776077; PMCID: PMC6450281.

Pantell RH, Roberts KB, Adams WG, Dreyer BP, Kuppermann N, O'Leary ST, Okechukwu K, Woods CR Jr; SUBCOMMITTEE ON FEBRILE INFANTS. Evaluation and Management of Well-Appearing Febrile Infants 8 to 60 Days Old. Pediatrics. 2021 Aug;148(2):e2021052228. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-052228. Epub 2021 Jul 19. Erratum in: Pediatrics. 2021 Nov;148(5): PMID: 34281996.

VACEP writeup

Burstein B, Alathari N, Papenburg J. Guideline-Based Risk Stratification for Febrile Young Infants Without Procalcitonin Measurement. Pediatrics. 2022;149(6):e2021056028

Easter JS, Haukoos JS, Meehan WP, Novack V, Edlow JA. Will Neuroimaging Reveal a Severe Intracranial Injury in This Adult With Minor Head Trauma?: The Rational Clinical Examination Systematic Review. JAMA. 2015 Dec 22-29;314(24):2672-81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.16316. Erratum in: JAMA. 2017 May 16;317(19):2021. PMID: 26717031.